_____ Proposed the Family Resemblance and Prototype Theories of Categorization.

Prototype theory is a theory of categorization in cerebral science, particularly in psychology and cognitive linguistics, in which there is a graded degree of belonging to a conceptual category, and some members are more central than others. It emerged in 1971 with the work of psychologist Eleanor Rosch, and information technology has been described as a "Copernican revolution" in the theory of categorization for its departure from the traditional Aristotelian categories.[i] Information technology has been criticized by those that notwithstanding endorse the traditional theory of categories, like linguist Eugenio Coseriu and other proponents of the structural semantics epitome.[ane]

In this image theory, any given concept in whatsoever given language has a real world instance that best represents this concept. For instance: when asked to requite an example of the concept furniture, a couch is more frequently cited than, say, a wardrobe. Prototype theory has also been applied in linguistics, every bit part of the mapping from phonological construction to semantics.

In formulating image theory, Rosch drew in part from previous insights in particular the formulation of a category model based on family resemblance by Wittgenstein (1953), and by Roger Dark-brown'southward How shall a thing be called? (1958).[2]

Overview and terminology [edit]

The term prototype, as defined in psychologist Eleanor Rosch's study "Natural Categories",[3] was initially defined as cogent a stimulus, which takes a salient position in the formation of a category, due to the fact that it is the first stimulus to exist associated with that category. Rosch later defined it as the near central fellow member of a category.

Rosch and others developed image theory as a response to, and radical departure from, the classical theory of concepts, which defines concepts by necessary and sufficient weather condition.[four] [v] Necessary atmospheric condition refers to the set of features every instance of a concept must present, and sufficient weather condition are those that no other entity possesses. Rather than defining concepts past features, the prototype theory defines categories based on either a specific artifact of that category or by a set of entities within the category that stand for a prototypical fellow member.[6] The epitome of a category can be understood in lay terms past the object or fellow member of a class most often associated with that class. The prototype is the middle of the form, with all other members moving progressively further from the prototype, which leads to the gradation of categories. Every fellow member of the grade is non equally central in homo noesis. As in the instance of furniture above, couch is more central than wardrobe. Contrary to the classical view, prototypes and gradations lead to an understanding of category membership not equally an all-or-zip approach, but equally more of a spider web of interlocking categories which overlap.

In Cognitive linguistics it has been argued that linguistic categories besides have a epitome structure, similar categories of mutual words in a linguistic communication.[7]

Categories [edit]

Bones level categories [edit]

The other notion related to prototypes is that of a basic level in cerebral categorization. Basic categories are relatively homogeneous in terms of sensory-motor affordances — a chair is associated with bending of one'due south knees, a fruit with picking it upwards and putting it in your mouth, etc. At the subordinate level (eastward.grand. [dentist's chairs], [kitchen chairs] etc.) few significant features can be added to that of the basic level; whereas at the superordinate level, these conceptual similarities are hard to pinpoint. A picture of a chair is easy to draw (or visualize), just cartoon furniture would be more hard.

Linguist Eleanor Rosch defines the basic level as that level that has the highest caste of cue validity.[8] Thus, a category similar [beast] may have a prototypical member, merely no cognitive visual representation. On the other hand, bones categories in [fauna], i.e. [dog], [bird], [fish], are total of advisory content and can easily be categorized in terms of Gestalt and semantic features.

Clearly semantic models based on attribute-value pairs fail to identify privileged levels in the bureaucracy. Functionally, information technology is thought that basic level categories are a decomposition of the earth into maximally informative categories. Thus, they

- maximize the number of attributes shared past members of the category, and

- minimize the number of attributes shared with other categories

However, the notion of Basic Level is problematic, e.k. whereas dog as a bones category is a species, bird or fish are at a higher level, etc. Similarly, the notion of frequency is very closely tied to the basic level, but is difficult to pinpoint.

More problems ascend when the notion of a prototype is applied to lexical categories other than the noun. Verbs, for instance, seem to defy a clear epitome: [to run] is hard to separate in more or less central members.

In her 1975 paper, Rosch asked 200 American college students to rate, on a scale of i to seven, whether they regarded certain items every bit good examples of the category article of furniture.[9] These items ranged from chair and sofa, ranked number 1, to a love seat (number x), to a lamp (number 31), all the fashion to a phone, ranked number 60.

While one may differ from this listing in terms of cultural specifics, the indicate is that such a graded categorization is likely to exist nowadays in all cultures. Further evidence that some members of a category are more than privileged than others came from experiments involving:

- 1. Response Times: in which queries involving prototypical members (due east.k. is a robin a bird) elicited faster response times than for not-prototypical members.

- 2. Priming: When primed with the higher-level (superordinate) category, subjects were faster in identifying if two words are the aforementioned. Thus, after flashing furniture, the equivalence of chair-chair is detected more than speedily than stove-stove.

- 3. Exemplars: When asked to name a few exemplars, the more prototypical items came upwardly more ofttimes.

Subsequent to Rosch's work, prototype effects have been investigated widely in areas such as colour cognition,[x] and also for more than abstract notions: subjects may exist asked, e.grand. "to what degree is this narrative an instance of telling a prevarication?".[11] Like work has been done on actions (verbs like expect, kill, speak, walk [Pulman:83]), adjectives like "tall",[12] etc.

Another aspect in which Image Theory departs from traditional Aristotelian categorization is that there do not appear to exist natural kind categories (bird, canis familiaris) vs. artifacts (toys, vehicles).

A common comparing is the use of image or the use of exemplars in category classification. Medin, Altom, and White potato found that using a mixture of paradigm and exemplar information, participants were more than accurately able to judge categories.[thirteen] Participants who were presented with prototype values classified based on similarity to stored prototypes and stored exemplars, whereas participants who only had feel with exemplar simply relied on the similarity to stored exemplars. Smith and Minda looked at the apply of prototypes and exemplars in dot-blueprint category learning. They constitute that participants used more prototypes than they used exemplars, with the prototypes being the center of the category, and exemplars surrounding it.[14]

Distance between concepts [edit]

The notion of prototypes is related to Wittgenstein'south (later) discomfort with the traditional notion of category. This influential theory has resulted in a view of semantic components more as possible rather than necessary contributors to the significant of texts. His discussion on the category game is particularly incisive:[xv]

Consider for instance the proceedings that nosotros call 'games'. I mean lath games, carte games, brawl games, Olympic games, then on. What is common to them all? Don't say, "There must be something mutual, or they would not be chosen 'games'"--merely wait and see whether in that location is anything common to all. For if you lot wait at them yous will not encounter something common to all, simply similarities, relationships, and a whole series of them at that. To repeat: don't recall, but look! Look for example at board games, with their multifarious relationships. Now laissez passer to carte games; hither yous discover many correspondences with the first group, but many mutual features drop out, and others appear. When we pass next to brawl games, much that is common is retained, simply much is lost. Are they all 'agreeable'? Compare chess with noughts and crosses. Or is there always winning and losing, or competition betwixt players? Think of patience. In ball games there is winning and losing; merely when a child throws his ball at the wall and catches it again, this feature has disappeared. Wait at the parts played by skill and luck; and at the difference between skill in chess and skill in tennis. Think at present of games like ring-a-ring-a-roses; here is the chemical element of entertainment, but how many other characteristic features accept disappeared! And nosotros can go through the many, many other groups of games in the same way; tin can see how similarities crop upwards and disappear. And the effect of this examination is: nosotros see a complicated network of similarities overlapping and criss-crossing: sometimes overall similarities, sometimes similarities of detail.

Wittgenstein's theory of family resemblance describes the miracle when people group concepts based on a series of overlapping features, rather than by i feature which exists throughout all members of the category. For example, basketball and baseball share the use of a ball, and baseball game and chess share the feature of a winner, etc, rather than one defining feature of "games". Therefore, there is a distance between focal, or prototypical members of the category, and those that proceed outwards from them, linked by shared features.

Recently, Peter Gärdenfors has elaborated a possible partial explanation of epitome theory in terms of multi-dimensional feature spaces chosen conceptual spaces, where a category is defined in terms of a conceptual altitude. More than primal members of a category are "betwixt" the peripheral members. He postulates that nearly natural categories showroom a convexity in conceptual space, in that if x and y are elements of a category, and if z is between ten and y, then z is likewise probable to belong to the category.[16]

Combining categories [edit]

Inside language nosotros notice instances of combined categories, such as alpine man or small elephant. Combining categories was a problem for extensional semantics, where the semantics of a word such as red is to be defined as the set of objects having this property. This does non apply also to modifiers such every bit small; a small mouse is very different from a minor elephant.

These combinations pose a lesser problem in terms of prototype theory. In situations involving adjectives (e.g. tall), i encounters the question of whether or not the paradigm of [alpine] is a 6 foot tall man, or a 400-foot skyscraper. The solution emerges past contextualizing the notion of prototype in terms of the object being modified. This extends even more radically in compounds such as red wine or red hair which are inappreciably cerise in the prototypical sense, but the crimson indicates just a shift from the prototypical color of vino or hair respectively. The add-on of red shifts the image from the one of hair to that of ruby hair. The prototype is inverse by additional specific information, and combines features from the prototype of red and wine.

Critique [edit]

Image theory has been criticized past those that still endorse the classic theory of categories, like linguist Eugenio Coseriu and other proponents of the structural semantics paradigm.[1]

Exemplar theory [edit]

Douglas L. Medin and Marguerite Thou. Schaffer showed past experiment that a context theory of classification which derives concepts purely from exemplars (cf. exemplar theory) worked amend than a grade of theories that included prototype theory.[17]

Graded categorization [edit]

Linguists, including Stephen Laurence writing with Eric Margolis, have suggested problems with the prototype theory. In their 1999 paper, they enhance several issues. One of which is that paradigm theory does not intrinsically guarantee graded categorization. When subjects were asked to rank how well certain members exemplify the category, they rated some members in a higher place others. For example robins were seen as existence "birdier" than ostriches, but when asked whether these categories are "all-or-nothing" or have fuzzier boundaries, the subjects stated that they were divers, "all-or-nothing" categories. Laurence and Margolis ended that "paradigm structure has no implication for whether subjects represent a category as beingness graded" (p. 33).[18]

Compound concepts [edit]

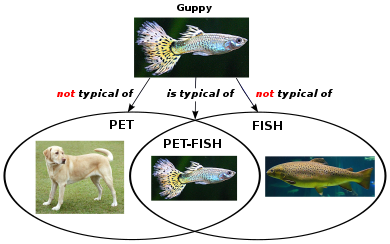

A guppy is not a image pet, nor a prototype fish, only it is a prototype pet-fish. This challenges the thought that prototypes are created from their constituent parts.

Daniel Osherson and Edward Smith raised the issue of pet fish for which the image might exist a guppy kept in a bowl in someone's house. The prototype for pet might be a dog or cat, and the prototype for fish might be trout or salmon. However, the features of these prototypes do not present in the image for pet fish, therefore this epitome must be generated from something other than its constituent parts.[xix] [twenty]

Antonio Lieto and Gian Luca Pozzato[21] have proposed a typicality-based compositional logic (TCL) that is able to business relationship for both complex man-like concept combinations (like the PET-FISH problem) and conceptual blending. Thus, their framework shows how concepts expressed as prototypes can business relationship for the phenomenon of prototypical compositionality in concept combination.

See also [edit]

- Composite photography

- Blended portrait

- Exemplar theory

- Family resemblance

- Folksonomy

- Frame semantics

- Ideal ideal

- Semantic feature-comparison model

- Similarity (philosophy)

- Intuitive statistics

Footnotes [edit]

- ^ a b c Coșeriu (2000)

- ^ Croft and Cruse (2004) Cognitive Linguistics ch.four pp.74-77

- ^ Rosch, Eleanor H. (1973-05-01). "Natural categories". Cognitive Psychology. iv (3): 328–350. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(73)90017-0. ISSN 0010-0285.

- ^ Rosch, Eleanor; Mervis, Carolyn B; Gray, Wayne D; Johnson, David M; Boyes-Braem, Penny (July 1976). "Bones objects in natural categories". Cerebral Psychology. 8 (iii): 382–439. doi:x.1016/0010-0285(76)90013-X. S2CID 5612467.

- ^ Adajian, Thomas (2005). "On the Image Theory of Concepts and the Definition of Art". The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. 63 (3): 231–236. doi:10.1111/j.0021-8529.2005.00203.x. ISSN 0021-8529. JSTOR 3700527.

- ^ Taylor, John R. (2009). Linguistic categorization. Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN978-0-19-926664-vii. OCLC 553516096.

- ^ John R Taylor (1995) Linguistic Categorization: Prototypes in Linguistic Theory, 2nd ed., ch.2 p.21

- ^ Rosch, Eleanor (1988), "Principles of Categorization", Readings in Cognitive Science, Elsevier, pp. 312–322, doi:x.1016/b978-i-4832-1446-7.50028-5, ISBN978-1-4832-1446-vii

- ^ Rosch, Eleanor (1975). "Cognitive representations of semantic categories". Periodical of Experimental Psychology: General. 104 (3): 192–233. doi:10.1037//0096-3445.104.3.192. ISSN 0096-3445.

- ^ Collier, George A.; Berlin, Brent; Kay, Paul (March 1973). "Basic Color Terms: Their Universality and Evolution". Language. 49 (ane): 245. doi:ten.2307/412128. ISSN 0097-8507. JSTOR 412128.

- ^ Coleman, Linda; Kay, Paul (March 1981). "Prototype Semantics: The English Word Lie". Language. 57 (1): 26. doi:10.2307/414285. ISSN 0097-8507. JSTOR 414285.

- ^ Geeraerts, Dirk; Dirven, René; Taylor, John R.; Langacker, Ronald Due west., eds. (2001-01-31). Applied Cognitive Linguistics, Ii, Language Didactics. doi:10.1515/9783110866254. ISBN9783110866254.

- ^ Medin, Douglas L.; Altom, Mark Westward.; Murphy, Timothy D. (1984). "Given versus induced category representations: Apply of epitome and exemplar information in classification". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 10 (3): 333–352. doi:ten.1037/0278-7393.x.3.333. ISSN 1939-1285. PMID 6235306.

- ^ Johansen, Mark K.; Kruschke, John 1000. (2005). "Category Representation for Classification and Feature Inference". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Retentiveness, and Cognition. 31 (half dozen): 1433–1458. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.31.6.1433. ISSN 1939-1285. PMID 16393056.

- ^ Wittgenstein, Ludwig (1953). Philosophical Investigations. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN978-1405159289.

- ^ Gärdenfors, Peter. Geometry of meaning : semantics based on conceptual spaces. Cambridge, Massachusetts. ISBN0-262-31958-6. OCLC 881289030.

- ^ Medin, Douglas Fifty.; Schaffer, Marguerite G. (1978). "Context theory of nomenclature learning". Psychological Review. 85 (three): 207–238. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.85.iii.207. ISSN 0033-295X.

- ^ Concepts : core readings. Margolis, Eric, 1968-, Laurence, Stephen. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. 1999. ISBN0-262-13353-9. OCLC 40256159.

{{cite volume}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Osherson, Daniel North.; Smith, Edward E. (1981). "On the capability of prototype theory as a theory of concepts". Knowledge. ix (1): 35–58. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(81)90013-5. ISSN 0010-0277.

- ^ Fodor, Jerry; Lepore, Ernest (February 1996). "The cherry-red herring and the pet fish: why concepts yet can't be prototypes". Cognition. 58 (two): 253–270. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(95)00694-x. ISSN 0010-0277. PMID 8820389. S2CID 15356470.

- ^ Lieto, Antonio; Pozzato, Gian Luca (2020). "A clarification logic framework for commonsense conceptual combination integrating typicality, probabilities and cognitive heuristics". Periodical of Experimental and Theoretical Artificial Intelligence. 32 (5): 769–804. arXiv:1811.02366. doi:10.1080/0952813X.2019.1672799. S2CID 53224988.

References [edit]

- Berlin, B. & Kay, P. (1969): Bones Color Terms: Their Universality and Evolution, Berkeley.

- Coseriu, E., Willems, M and Leuschner, T, (2000) Structural Semantics and 'Cognitive' Semantics, in Logos and Language

- Dirven, R. & Taylor, J. R. (1988): "The conceptualisation of vertical Infinite in English: The Case of Tall", in: Rudzka-Ostyn, B.(ed): Topics in Cognitive Linguistics. Amsterdam.

- Galton, F. (1878). Composite portraits. Journal of the Anthropological Found of Great U.k. and Ireland, Vol.8, pp.132–142. doi=10.2307/2841021

- Gatsgeb, H. Z., Dundas, Due east. M., Minshew, Yard. J., & Strauss, M. S. (2012). Category formation in autism: Can individuals with autism course categories and prototypes of dot patterns?. Journal of Autism and Development Disorders, 42(8), 1694-1704. doi:10.1007/s10803-011-1411-x

- Gatsgeb, H. Z., Wilkinson, D. A., Minshew, Thousand. J., & Strauss, Chiliad. Due south. (2011). Tin can individuals with autism abstract prototypes of natural faces?. Journal of Autism and Development Disorders, 41(12), 1609-1618. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1190-4

- Gärdenfors, P. (2004): Conceptual Spaces: The Geometry of Thought, MIT Printing.

- Lakoff, Thou. (1987): Women, fire and dangerous things: What categories reveal about the heed, London.

- Lieto, A., Pozzato, One thousand.L. (2019): A description logic framework for commonsense conceptual combination integrating typicality, probabilities and cognitive heuristics, Journal of Experimental and Theoretical Artificial Intelligence, doi: 10.1080/0952813X.2019.1672799.

- Loftus, E.F., "Spreading Activation Inside Semantic Categories: Comments on Rosch's "Cerebral Representations of Semantic Categories"", Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, Vol.104, No.3, (September 1975), p. 234-240.

- Medin, D. L., Altom, Grand. W., & Murphy, T. D. (1984). Given versus induced category representations: Use of paradigm and exemplar information in classification. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, ten(iii), 333-352. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.ten.3.333

- Molesworth, C. J., Bowler, D. M., & Hampton, J. A. (2005). Extracting prototypes from exemplars what tin can corpus information tell us about concept representation?. Journal of Kid Psychology and Psychiatry, 46(6), 661-672. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00383.x

- Molesworth, C. J., Bowler, D. M., & Hampton, J. A. (2008). When prototypes are non best: Judgments made by children with autism. Journal of Autism and Evolution Disorders, 38(9), 1721-1730. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0557-seven

- Rosch, E., "Classification of Real-World Objects: Origins and Representations in Knowledge", pp. 212–222 in Johnson-Laird, P.Due north. & Wason, P.C., Thinking: Readings in Cerebral Science, Cambridge University Press, (Cambridge), 1977.

- Rosch, Due east. (1975): "Cerebral Reference Points", Cognitive Psychology vii, 532-547.

- Rosch, E., "Cognitive Representations of Semantic Categories", Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, Vol.104, No.iii, (September 1975), pp. 192–233.

- Rosch, E.H. (1973): "Natural categories", Cognitive Psychology four, 328-350.

- Rosch, E., "Principles of Categorization", pp. 27–48 in Rosch, E. & Lloyd, B.B. (eds), Cognition and Categorization, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers, (Hillsdale), 1978.

- Rosch, E., "Prototype Classification and Logical Classification: The Two Systems", pp. 73–86 in Scholnick, Eastward.Thousand. (ed), New Trends in Conceptual Representation: Challenges to Piaget's Theory?, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, 1983.

- Rosch, East., "Reclaiming Concepts", Journal of Consciousness Studies, Vol.6, Nos.11-12, (Nov/December 1999), pp. 61–77.

- Rosch, E., "Reply to Loftus", Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, Vol.104, No.3, (September 1975), pp. 241–243.

- Rosch, E. & Mervis, C.B., "Family unit Resemblances: Studies in the Internal Structure of Categories", Cognitive Psychology, Vol.7, No.four, (Oct 1975), pp. 573–605.

- Rosch, Eastward., Mervis, C.B., Gray, Due west., Johnson, D., & Boyes-Braem, P., Basic Objects in Natural Categories, Working Paper No.43, Language Behaviour Research Laboratory, University of California (Berkeley), 1975.

- Rosch, Eastward., Mervis, C.B., Gray, Due west., Johnson, D., & Boyes-Braem, P., "Bones Objects in Natural Categories", Cognitive Psychology, Vol.8, No.three, (July 1976), pp. 382–439.

- Smith, J. D., & Minda, J. P. (2002). Distinguishing image-based and exemplar-based processes in dot-design category learning. Periodical of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Retention, and Cognition, 28(iv), 1433-1458. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.31.half-dozen.1433

- Taylor, J. R.(2003): Linguistic Categorization, Oxford University Press.

- Wittgenstein, L., Philosophical Investigations (Philosophische Untersuchungen), Blackwell Publishers, 2001 (ISBN 0-631-23127-seven).

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prototype_theory

0 Response to "_____ Proposed the Family Resemblance and Prototype Theories of Categorization."

Post a Comment